In these new and uncertain times, pupils will have spent many months away from school due to the closures put in place as a result of Covid-19.

Schools in England were closed to all pupils except those of key-workers and vulnerable children on the 20th March 2019 and have only reopened to certain pupils in the last few weeks.

Learning has been disrupted and will have been lost.

As this is an unprecedented situation in the UK, there is no previous research that can show us what the educational impact of COVID-19 school closures might be.

Never in our lifetimes have so many schools been closed for so many children.

We prize attendance in our schools and often use posters like this to make children and parents aware of why time at school is so important. But what happens if the whole school is closed and everyone stops attending?

Has this happened before..?

Closed Schools

Studies of previous school closures abroad show a real negative impact on learning.

In 1968, teacher strikes closed public schools in New York City for more than two months and also closed French Belgian schools for more than two months in 1990.

When students returned to New York City schools after the two-month strike of 1968, their test scores were about two months lower, on average, than children’s scores the previous year.

French-speaking Belgian students affected by the 1990 strike were more likely to repeat a grade and did not advance as far in higher education as similar Flemish-speaking students whose teachers did not strike.

Another example is a natural disaster such as Hurricane Katrina where test scores fell sharply among New Orleans children whose schools closed, or the severe floods in Thailand which deeply affected learning outcomes across all grade levels.

The simple fact is that children who are not in school learn less, despite the best intentions of distance education and home schooling, and this is particularly shown in areas with higher proportions of disadvantaged and minority children.

Summer Learning Loss

In America, the NSLA (the national summer learning association) has led the charge, writing books and encouraging summer learning programmes to be established in school districts across the country.

Their conviction is based on research that has found that students can lose up to two months of academic growth across the holidays.

A review of 39 studies back in 1996 looked at research into achievement test scores for over 50,000 students and suggested that they experience an average summer learning loss estimated to equal about one month of the academic year. The effect of the summer holidays is typically more detrimental for Maths and spelling.

The studies also indicated a clear link between socioeconomic status and level of learning lost during the summer holidays. It was found that after the summer holidays, middle class students showed no change in their reading and language abilities, whilst students of a lower socio-economic status saw their abilities diminish. This created a gap between these students that was equivalent to three months.

NWEA Study

Taking this analysis a step further and to the present crisis, Beth Tarasawa and Megan Kuhfeld, researchers for NWEA, the Northwest Evaluation Association in America, analysed student achievement and growth data from more than 5 million students in grades 3-8.

The researchers used this data to project growth trajectories for the students with reference to the learning lost due to the COVID shutdown. First they showed an academic “melt” where all learning stood still.

However, with no learning taking place, this soon became a “slide”.

The forecast here shows that pupils could lose more than 70% of their reading progress.

This slide is shown even more markedly in their forecast for mathematics. Depending on the grade, they projected that students could lose up to all of their academic growth from the previous year.

Comparing the current crisis with summer learning loss is difficult and problematic due to the simple fact that although school buildings have closed, schools themselves have moved to provide home learning opportunities.

In this crisis – Learning has not stopped outright (or has it?)…

Home Learning

Since the 20th March, with the exception of the school holidays, all learning now takes place remotely. Some schools have adapted very well and with the arrival of BBC Bitesize and Oak National, there have been a lot of really positive changes.

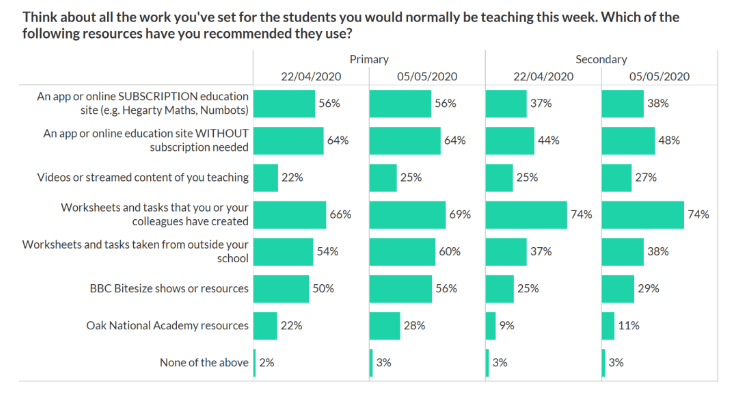

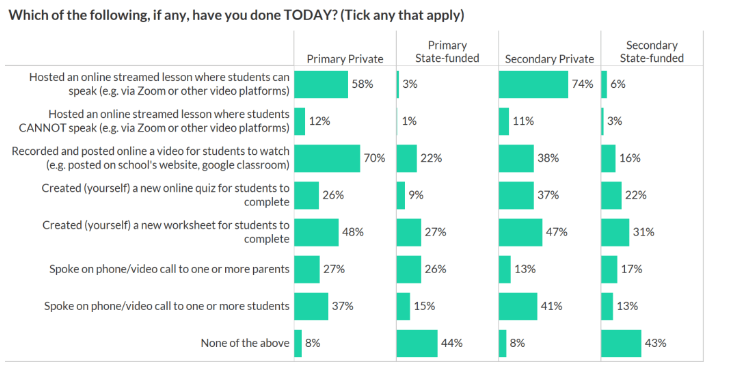

Teachers have had to adapt too with lessons now online and other resources being created as research by Teacher Tapp has found..

However, a recent report by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) has stated that despite teachers being in regular contact with, on average, 60% of their pupils – most teachers believe that their pupils are doing less or much less work than they would normally at this time of year.

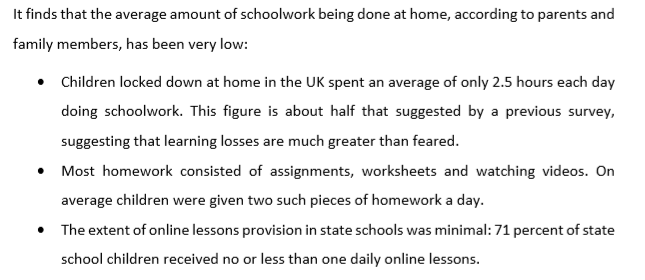

This NFER study is echoed by a research paper from University College London’s Institute of Education which examined data from a UK household longitudinal study covering 4,559 children.

This figure is about half that indicated by a previous survey by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, suggesting that learning losses could be much greater than previously thought.

This is not surprising – take a child out of a classroom context and you lose a lot of the peer motivation that school dynamics is built around and simply cannot be replicated at home.

What is more worrying though here is the engagement of the most vulnerable pupil groups.

Teachers are concerned about the engagement of all their disadvantaged pupils, but are most concerned about low engagement from pupils with limited access to IT and/or those who lack space to study at home.

They report that the following proportions of disadvantaged pupils are less engaged in remote learning than their classmates:

Pupils with limited access to IT and/or study space (81 per cent)

Vulnerable pupils (62 per cent)

Pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (58 per cent)

Pupils eligible for Pupil Premium funding (52 per cent)

Young carers (48 per cent).

NFER: schools-responses-to-covid-19-pupil-engagement-in-remote-learning/

Remote Learning Support

One of the major impacts here is what has now become known as the “digital divide.”

Wayne Norrie, chief executive of Greenwood Academies Trust, which has three dozen schools across England, told The Independent:

“Remote learning and digital resources have been vital in supporting children’s learning during school closures. However, serving a high proportion of disadvantaged families, approximately 60 per cent across the trust, we recognise the extent of some parents’ struggles to support their children during this difficult time, including providing reliable internet access.”

The NFER research asked senior leaders what proportion of pupils have little or no access to IT at home.

The answer was nearly 25% of pupils.

This creates huge issues for home learning and is a clear issue worldwide – a quick look at #digitaldivide on twitter brings up stories in America, Australia, India, Canada amongst others.

Here in the UK, the government announced that vouchers for free internet access are to be given to poorest families amid fears disadvantaged children are falling behind but this is a step too late.

Have a look at the difference of work set by private and state-funded schools. Note the level of online streaming..

The further issue here is how we are now relying on the IT infrastructure to take the place of a qualified and skilled teacher. As summer learning researcher Paul T. von Hippel explains..

“Most ed tech products were meant to supplement school, not to replace it outright, and some functions of school are hard to replace, especially when it comes to younger children and softer skills. A third grader learning arithmetic facts may do pretty well with adaptive software drills, and a self-starting high school senior may be able to prepare for AP exams using emailed assignments and practice tests. But for a kindergartener who needs to learn not to cut line, yell, or hit classmates, technology is not much of a solution. Reluctant first grade readers who’ve never had more than 30 minutes of homework may cause trouble when they see their first emailed assignment. And children with serious learning disabilities may be seriously out of luck.”

“how-will-coronavirus-crisis-affect-childrens-learning-unequally-covid-19”

Change in Environment

The other buffer to home learning is parents and the home situation. At school, children can focus on one thing – their education. With other distractions like games consoles, the warm weather and simply the change of environment, it is little wonder that pupils will not be able to concentrate as they do at school.

The NFER research reported that, on average, just over half (55%) of their pupils’ parents are engaged with their children’s home learning. Parental engagement is significantly lower among the parents of secondary than primary pupils – more than likely influenced by the age of the pupils. This is still very different from the classroom scenario where learning usually takes place.

We must also throw in this conversation the worries that covid-19 brings to every member of the family. With many people furloughed and no longer sure of a financial future, priorities can change as Paul T. von Hippel continues..

“Parents, though, are even more unequal than technology. An only child with two college-educated parents may get a lot of help and enrichment—particularly if those parents are financially secure, have flexible work arrangements, and aren’t too freaked out by news and social media. But consider a single parent with three children and a high-school education. Her children will have to compete for her attention, and when they get it, it’s less likely she can help them with homework and technology. If the parent has just lost her job, fears infection, and has less than a month of expenses in the bank, helping her second grader with schoolwork may seem like a low priority. As one mother of four told the Associated Press, “My worry is survival, not conjugating verbs.”

“How-will-coronavirus-crisis-affect-childrens-learning-unequally-covid-19”

There is therefore a call for caution and the need for teachers to aid children in their “recovery”. As Rebecca Brooks, AUK Education Policy Advisor, states in her blog for Adoption UK..

“What children need – in fact what society needs – after the pandemic is not ‘catch up’. It is ‘recovery’.

‘Catch up’ implies a narrow emphasis on curriculum goals with a focus on getting all children to the same end point as quickly as possible. ‘Recovery’ acknowledges that the impact of this crisis has been far wider than ‘missed learning’ and that we will need to begin where children are, rather than focus on where we would like them to be, and how to get them all to that same point as quickly as possible.

Some will return to education having made surprising progress, not only in learning of all kinds, but also in terms of their mental health and wellbeing, which are foundational to learning success. Others may have maintained their learning to a degree, but be carrying an emotional burden which will guarantee that they buckle under the pressure of ‘catch up’ programmes. Still others will arrive on shaky ground in all areas, having endured a period of their lives where survival was the only attainable goal.”

“The-myth-of-catching-up-after-covid-19”

The fact is, with students now facing up to 6 months without consistent guidance from teachers and the structure offered by the classroom environment, and with 55% of teachers from the most disadvantaged areas reporting concerns that their students are learning for less than one hour each day, researchers have estimated that disadvantaged students could be facing learning losses of between four and six months.

The way forward

The answers are not simple or straight forward. As Leona Cruddas, CEO of the Confederation of School Trusts, said to the Education Select Committee in Parliament..

“Learning loss can’t be known until children are back in school and can be assessed. We can close the learning gap – trusts can and do rapidly put in place recovery curricula. It is a long-term issue, but doable.“

DAISI Education

Thank you for reading this article.

Find other Blog articles by clicking here

Check out more about how we can help your school: Primary | Secondary

Really interesting debate here. Thank you.

Thank you for the feedback.

I’m really not sure that any of this learning loss will affect students in the long run. SATs are a waste of time anyway and secs will compensate. GCSEs will be marginally affected, but there are other ways to judge – as per this year for next year’s Y10. Universities will understand and compensate. So why is such a song and dance being made?

Thank you for your feedback.

Fascinating blog – really interesting

Thank you for the feedback.

Really insightful discussion and Impressive research.

Thank you. We believe it is a really important discussion to be had. It is right we work to allow each pupil to still realise their potential regardless of covid-19.

More than a third (36%) of pupils at primary level eligible for free school meals and a quarter (26%)of pupils at secondary level are spending just an hour or less on school work a day since schools closed, a new survey by the University of Sussex has revealed. Article in Tes: https://www.tes.com/news/coronavirus-1-3-primary-fsm-pupils-learning-hour-day

Thank you for this. We are looking at ideas for what to do to help students when they return in september. Really good read.

Are you Secondary or Primary? Have a look at our Question Level Analysis – https://daisi.education/qla/

We are currently working on scaled down versions of SATs tests to make the testing more manageable but giving the same detailed analysis. Watch this space…

Thank you for this – really interesting discussion. Will be showing to my fellow governors

Thank you. Please share..